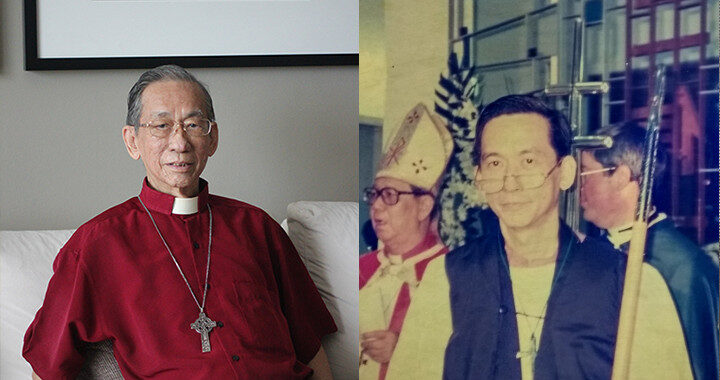

The Right Reverend Yong Ping Chung served full-time in the Anglican Diocese of Sabah for 37 years beginning in 1969, first as a priest, then as archdeacon and finally as Bishop of Sabah for 16 years (1990-2006). He also was elected as the second Archbishop of the Province of South East Asia (2000-2006). This year marks 51 years since he was ordained, and he continues to assist with preaching and confirmation around the Diocese. The first part of this interview focused on his childhood as well as his journey to and early years in ordained ministry. In this second part of this interview with him at his home in Kota Kinabalu, he speaks about his involvement in the international Anglican Consultative Council (ACC), his election as Bishop of Sabah, as well as some of the joys and challenges he faced while serving as the bishop of a diocese which often lacked resources and which was also quite diverse in terms of theological and other opinions among its people.

Aside from being involved in the diocese, am I right that you were also very involved in the global scene, for example, with the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC)?

Well, I think in a way that was an accident. [laughs] Soon after I came back, I represented our diocese at the Council of the Church of East Asia (CCEA). At the CCEA meeting they elected me to represent them at the ACC. At the ACC, I was, I suppose, a little bit more vocal compared to some of the non-English-speaking members who didn’t speak up very much. As a result, I was elected onto the Standing Committee of the ACC, and then later as Chairman of the ACC.

How long were you the ACC chairman and what were your duties?

The chairman is always elected for two terms, which is around six to eight years. My duties included attending standing committee meetings and going to England to meet the Archbishop of Canterbury. The ACC’s purpose is for consultation, for the global Anglican leadership to hear what is going on on the ground around the world.

I see. Some time later you became Bishop of Sabah?

Yes, in 1990.

When you became the Bishop, how did you feel when you were given this weighty responsibility?

Well, by that point I had been in the diocese for a long time, and I suppose I was also the most experienced priest, as I had been into the interior and everywhere else. So, when the time came for the appointment of a new bishop, the diocese had a meeting and submitted potential candidates. The decision-maker felt that I should take up the responsibility, so I thought, “Okay, if that is what God wants, I had better accept it.” The wonderful thing is that God has promised us that his grace is sufficient. So it’s not up to me. It’s God’s grace. God doesn’t promise us success. He says, “My grace is sufficient.” And what he means is, “You follow my grace.”

What are some of the challenges that the Bishop of Sabah faces?

Bishop Chhoa was the Bishop of Sabah for 17 years. I was Bishop for 16 years. These were, in a way, difficult times. We didn’t have sufficient priests and we didn’t have a lot of money. But thankfully from the very beginning we taught tithing and that the ministry belongs to the people, so the support has to come from the people. Support here means both manpower and finance. Our principle was that we used only what we had. We didn’t use whatever we didn’t have. You see, a lot of other overseas dioceses depend very much on the support from mission agencies in England, America, Australia and so on. But as for us, our programmes and so on were tailored to the resources we had. If we needed to raise money, we raised it from inside, from our own people.

That’s a very good but also very radical policy, because it’s easier to depend on funding from missionary organisations.

Yes, if you depend for your support on the outside you’re in a comfort zone. For a long time our priests came from the outside, and we didn’t have to pay for them. If we needed a priest, we wrote to the USPG or CMS. And, lo and behold, three months later, the priest would arrive. We enjoyed their efforts but it was the mission organisations that paid the salaries. I think that’s not quite correct. So we wanted to be independent financially.

That’s great. Speaking about diocesan programmes and endeavours, would you tell us a little bit about Mission 113?

Mission 113 was a mission strategy that we started while I was bishop. Every believer would bring another person to become a believer every three years. The idea was also that for three years you would be responsible as a Christian for a new Christian, until they could walk for themselves. The theory was also that, if our people could fulfil this undertaking, we would double our attendance every three years. In the end our growth was not as fast as we aimed for, but we did double our attendance after about 10 years, from around 9,000 people to 18,000.

It was at this time, actually, that we began to count attendance rather than the number of people on the parish electoral roll. This was because a lot of people say they’re Anglican—they get baptised and confirmed—but they never live as Christians.

Very true. I understand that another development during your time as Bishop was the growth of the Charismatic Revival in the Diocese?

Yes, though the Charismatic Movement was growing all over Sabah, not just in the Anglican Church. We insisted on a Biblical approach. Our simple rule was that if you could find something in the Bible, you could practise it. But if you couldn’t find it in the Bible, then you couldn’t practise it. Our aim was not to be rigid, but to help people be free to do what they felt helped them grow spiritually.

I guess we can now say that the Charismatic Movement has been integrated very much into the life of the diocese?

Yes, I think we absorbed it. However, at that time some of our priests left us, saying, “We are Charismatic. The Anglican Church is dead.” We tried to persuade them by saying, “If you think the Charismatic Movement is good, why don’t you try to help the Diocese grow in this area?” So some did stay, even as a few left.

Was it a disappointment for you when they left?

Yes, of course. It was a great disappointment, especially as they were very good priests, with initiative and drive. But looking back now, since they left they’ve actually done quite well in their respective ministries. I comfort myself in the fact that it is the growth of the Kingdom of God, and not the Diocese of Sabah, that is the most important.

I guess over your long life and ministry you’ve experienced the diocese in its different periods. To use churchmanship as an example, initially the SPG missionaries were High Church. CMS missionaries then came with their Evangelical tradition, and beginning in the 1980s many seminarians went to Evangelical theological colleges. Later the Charismatic Movement came to prominence. Would you say the Diocese has benefited from all these things coming together?

I think we have managed to come together and tolerate each other, recognising that each of us has our own strengths and weaknesses. I think encouraging tolerance and acceptance of each other is a good thing, because this is a family mah. Members of a family are often very different. I think the diocese has become what it is today because we have been very carefully trying to encourage an overall broad acceptance of each other. Even in the Sabah Council of Churches we try to encourage the various churches to accept and work with each other. In a sense we Anglicans have become the “middle way.” One very interesting thing is that when we have an inter-church meeting, if we need to celebrate Holy Communion, they always ask us Anglicans to do it.

Given all these changes and with new things always coming in, has there been anything that has been lost from earlier times that you wish had been preserved?

Well, when I first came back to the cathedral, there was this “old-style” daily Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, and once during the week we had Holy Communion. I think that is not practised any more. That is something I think is a loss lah. Nowadays we encourage free devotion and doing your own thing. Sadly, this freedom can sometimes turn into not doing any devotions at all.

In the next and final part of the article, Bishop Yong Ping Chung shares about some of the highlights and most difficult moments while serving as Bishop of Sabah and as Archbishop of South East Asia, as well as his words of advice for those who feel called to full-time ministry.